America Has So Much More to Lose

"Civil War" is political without being overtly partisan, which speaks to today’s politics more than many realize

The following article includes major spoilers for Civil War. It’s for people who’ve seen the movie, people who don’t plan to, and anyone who might see it but doesn’t care if they know what happens.

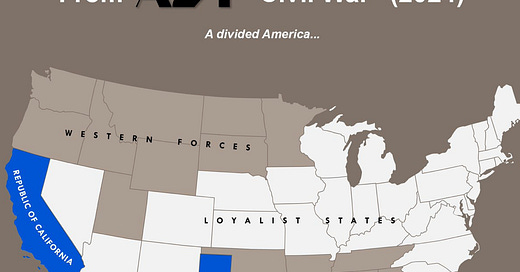

Civil War has been controversial since the first ads appeared, though perhaps not in the way its makers expected. Promos included a fictional near-future map of a divided America whose plausibility drew doubts, especially the alliance between California and Texas.

That criticism only increased after people saw the movie, which drops viewers into the middle of a war-torn United States without saying how it started or what various sides want. For example, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat lambasted Civil War as “overly pleased with its decision not to even try to invent a plausible path to its scenario.”

He’s wrong, and inadvertently highlights why the message matters. Shortly before the 2020 election, Douthat confidently declared “There Will Be No Trump Coup.” After January 6, he admitted he underrated the possibility then, but went right back to telling people concerned about the stability of Constitutional democracy that they should stop worrying. At best, this displays a lack of imagination, perhaps willfully so. Many Americans are, for a variety of reasons, stuck in a can’t-happen-here complacency, as if the future must look somewhat like the past, and the system they were born into is inherently self-sustaining.

It’s not. What sustains it is a politics beyond Democrat-Republican partisanship, one that requires regular tending and renewal. In that sense, much of the criticism that Civil War lacks “politics” is frustration that it doesn’t take a stance on today’s partisan fights. Viewers can’t quote the movie to tell any current faction “this is what’ll happen if you don’t stop.”

However, Civil War is very critical of some current real-world political actors—just not named politicians or parties. But many Americans put all U.S. politics, sometimes all world events, through a partisan frame, unwilling to consider, perhaps even unable to conceive, of American politics beyond partisanship.

In 2024 and likely beyond, U.S. democracy—and global stability—need them to.

Civil Conflict Isn’t Orderly

Civil War follows a group of war journalists driving from New York City to Washington DC on a long-route via Pennsylvania and West Virginia. Interstate highways are impassable, densely populated areas chaotic, and the DC area outlawed journalism. Everywhere they go, there’s violence and social breakdown.

Desperate people line up to get water and shoving escalates to fights, including with police. A suicide bomber sprints into a crowd and explodes. The UN runs a tent camp for displaced people. Snipers duel near a town’s never-cleaned-up Christmas display without knowing who’s trying to kill them.

In the background, there’s often a building on fire, damaged property, abandoned vehicles. There’s frequent sounds of gunfire, and sometimes visible tracer rounds. A body lies in the street, just left there as if nobody dare touch it, or nobody cares.

That’s what most civil conflict looks like today: Collapsing into chaos, with armed groups and individual criminals taking advantage. Sometimes there are two main sides fighting for control at the highest level, sometimes three or more, but it always causes severe disruption to law, order, commerce, and social life.

21st century civil wars and failed states in Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen have killed upwards of a million people combined, and harmed millions more. There are food and medicine shortages, and difficulty getting supplies into conflict zones. You can look up how those wars started, and who the main sides are, but you don’t need to know that to understand how it’s awful for people caught up in it.

If there’s another American civil war, it’ll probably look more like that than like Confederacy v. Union, which unfolded like an interstate war between neighbors.

Hollow Out the Middle

By showing the everyday horrors of societal breakdown, the movie takes on everyone romanticizing civil war and revolution, fantasizing about authoritarian rule, or claiming 2024 America is such a horrific dystopia that breaking it would be better. In that way, Civil War is more insightful about the current political moment than pundits and political junkies still caught up in normal Democrat-Republican partisanship.

Ours is a time of left-right division, of polarization, yes, but also of rising extremes, where politics looks more like a horseshoe than a spectrum. The danger in the United States, multiple other democracies, and to some extent the world, recalls the famous William Butler Yeats poem:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Civil War can’t prophesize how we get from here to there, but it’s right that American collapse would suck. There’s no amicable “national divorce,” no tough-talking podcasters living like kings, no thriving protest movement, no socialist revolution. The only ones who seem happy are an armed group that wins a firefight and executes their captives, the war journalists who get a rush from proximity to combat and get famous by documenting it, and maybe the residents of one weird town that seems untouched by the war.

But while that town is clean and functional, with a bored young woman working at a clothing store who says she doesn’t pay attention to the news, there’s no one on the street. No sounds of children. Turns out there’s armed men on rooftops, warily eyeing the outsiders—and overseeing the residents as well—in an environment the older Black journalist (Stephen McKinley Henderson) finds all too familiar.

In this war-torn society, living something approximating a normal life—by April 2024 U.S. standards—requires geographic isolation and extraordinary measures that come with downsides.

The only people thriving are the worst, unleashed by the collapse of law and order. In the movie’s tensest scene, a nationalist militia member (Jesse Plemons) toys with the journalists at gunpoint, asking each where they’re from, sparing the white women who say Colorado and Missouri because they’re “America,” then casually killing the Asian man who says Hong Kong.

The militia is dumping bodies into a mass grave, and we never find out who or why. That might bother viewers who want explanations, but it resembles real-world civil wars, not only in the unmarked mass grave, but also in the armed sociopaths enjoying intimidation and violence against strangers, with innocent people killed due to wrong place wrong time, or because some bigot hates their race.

What prevents that sort of thing is a state with, as per Max Weber’s classic definition, a monopoly on the legitimate use of force.

While the United States government fails to address some important problems, and has caused or worsened some, for the vast majority of Americans, the vacuum of a collapsed government would be much worse.

We Live in a Society

The combat scenes in Civil War are thrilling or disturbing (or both), but the best warnings come from non-violent encounters that highlight the collapse of social trust. There are roadblocks and ID checks, widespread assumptions of ulterior motives, and extreme wariness of strangers, even regarding basic economic interactions like buying gas.

On their long, backroads drive, the journalists see a gas station, and debate what to do. They see men with guns on guard, and their vehicle still has half a tank, but fuel is scarce enough that they decide it’s worth the risk. The gas station owners don’t know them or which faction they’re with, and aren’t sure about claims of press neutrality. They tell the journalists to move on, the journalists say they can pay “300,” the owner scoffs, but then hears a crucial follow-up: “300 Canadian.” He accepts.

One can mock the scene as unrealistic—the mighty U.S. dollar rejected, but Canada’s gets respect? Lol—but that’s too stuck in the present.

The U.S. dollar is backed “by the full faith and credit of the United States.” It has value because people around the world believe it does, in part because the world’s most powerful country says it does, offers things of value in exchange, and accepts it for required tax payments. If America collapses into civil conflict, the county’s full faith and credit doesn’t count for much. Especially if the president and Washington DC’s side looks like it’s losing.

The implausible part is not that U.S. money has declined in value, but that Canada is in good shape. Another near-future American dystopia, The Handmaid’s Tale, makes a similar mistake, with Canada providing a safe haven for escapees. But as political scientist Paul Musgrave explains, “moving to Canada won’t save you.” U.S. power is too great.

If the U.S. falls apart, Canada and Mexico would be dragged down, and possibly in. More broadly, the bedrock of the post-WWII and especially post-Cold War international system would be gone. That disintegration would make Civil War look pleasant.

Besides “300 Canadian,” the movie doesn’t mention the outside world—nor should it, that’d be distracting—but in the domestic setting, it shows how social trust is valuable, fragile, and hard to get back once lost.

That’s a political message people need to hear. Not that you should be content with the status quo or nostalgic for the recent past, but that the American democratic system—by which a large, diverse population makes collective decisions without killing each other—is worth conserving.

Reject “it can’t happen here” complacency. Identify real problems, but don’t give in to doom and gloom. Don’t fall for claims that the country’s gone to hell, that it’s already so terrible that tossing aside principles is necessary, or that we might as well burn it all down.

The California-Texas Alliance: Power and Principle Over Partisanship

The political arrangement in Civil War is not as implausible as its detractors say. California and Texas partnering against DC defies logic if you use a 2024 partisan frame. But use a hard power frame, and the most salient condition in the movie is that the U.S. military has split.

On January 6, 2022, the first anniversary of the attack on the U.S. Capitol, I wrote a piece called “How to Defend American Democracy.” One long-term goal I identified was “don’t let the military split.” In Civil War, Lee (Kirsten Dunst) is famous for photographing “the Antifa massacre” when she was in school—whether Antifa got massacred or did the massacring, the movie leaves ambiguous—and the actress is 41, so that’s about 18 years since college; a long time to witness atrocities, and for American stability to decline.

So yes, over a decade-plus time horizon, I think it’s plausible the U.S. military splits. I don’t think it’s likely or imminent, but the risk over time is sufficiently above zero that the national security community should treat it as a serious concern.

Noting that some former and even active duty members of the U.S. military participated in Jan. 6, retired Army generals Paul D. Eaton, Antonio M. Taguba and Steven M. Anderson issued a warning about the aftermath of the 2024 election: “The potential for a total breakdown of the chain of command along partisan lines — from the top of the chain to squad level — is significant should another insurrection occur. The idea of rogue units organizing among themselves to support the ‘rightful’ commander in chief cannot be dismissed.”

If central control of the U.S. military fell apart—another possibility is a rogue president giving a horrific illegal order that most refuse but others carry out—then California, Texas, and Florida make sense as power centers. A lot of domestic military assets are stationed there, and they have large National Guard and police to build their forces.

With law and order gone in much of the country, and chaos spiraling out from the U.S. military split, California and Texas would have bigger things on their mind than culture war. They’d have an interest in cooperating on the Mexico border(s), even though there would be much less north-bound migration. And if their combined military strength were enough to defeat the the corrupt president’s faction—especially if DC is dealing with forces from Florida and the northwest as well—they’d have a good reason to rush for Washington and remove him.

The only things Civil War tells us about the president (Nick Offerman) is he’s in an unconstitutional third term, dismantled the FBI, ordered the killing of journalists, and lies to the public that his forces won a big victory even as they keep falling back.

You know what would be better than red states and blue states uniting to stop a president like that after America collapses? Doing it in advance.