Would it not be a good regulation to oblige every member of Congress … to lay his hand on his heart and to declare that he is no speculator; and that he did not come forward to claim for himself the price of the blood or the limb or the life of the poor soldier … ?

—“A Farmer,” Maryland Gazette, February 26, 1790

When both Democratic and Republican lawmakers introduced bills early last year to ban members of Congress from trading individual stocks, the measures appeared destined for quick passage.

The basic idea of discouraging lawmakers from using their office to pursue their private interests rather than the public interest seemed like a no-brainer. The bills met with the robust approval of the general public across all political affiliations and a remarkable level of bipartisan favor in Congress—especially in these times of polarized gridlock.

Moreover, the 2012 STOCK (Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge) Act that was previously intended to prohibit members of Congress from trading using insider information had proven hard to enforce and ineffective. A recent study by several news organizations found that 78 members of Congress had violated the law, with little or no penalty.

Yet when the bills were first introduced in 2022, then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi initially dismissed the idea. “This is a free market and people,” Pelosi remarked. “They (lawmakers) should be able to participate in that.” She later expressed openness to a proposal provided House members could marshal the votes for one, although she remained personally opposed, stating, “I do believe in the integrity of people in public service.” When the 2022 Congress dragged its feet on the stock ban proposals, Pelosi introduced her own bill. But the House voted it down amid grumbling from some observers who accused legislative leaders of sabotaging it with conflicting provisions to make it unacceptable to the greatest number of representatives. Although new bills to ban stock trading have been introduced to the current Congress, skepticism over the will of U.S. lawmakers to act on them remains.

It now seems that lawmakers may have to be shamed into passing a stock trading ban. If so, it might help to revisit a brief but charged and disturbing episode of American history, what James Madison called “an enormous and flagrant injustice,” when the Congress of 1790 approved a financial policy that, in effect, enriched almost half of its mostly wealthy members by ripping off mostly poor Revolutionary War veterans.

Historians have generally ignored or dismissed this episode as a minor blip in the epic creation story of the U.S. But the fact remains that at the very founding of this country, Congress was rife with conflicts of interest, which cleaved an early rift of mistrust between the federal government and the people, and cast a shadow on the moral character of the new republic.

The principle behind the stock trading bans thus pertains not only to the present and future. It could also be seen as a recognition, if not redress, of a past offense, an unpaid moral and monetary debt of Congress to the American people, after 233 years.

In 1790, there was already ample cause for Americans to feel mistrust, if not disgust, towards their government. Weakly organized under the Articles of Confederation that were in effect until 1789, a cash-strapped, feckless, and fractious Congress was unable or unwilling to control rampant and widely known corruption in the military supply lines during the Revolutionary War (1775-1783). This failure exacerbated the difficulties and privation the soldiers faced and depleted government funds to prosecute the war. With hard money (gold and silver) or “specie” scarce, the states individually and Congress nationally issued paper money to keep the economy going. But uncertainty over the values of the various currencies led to their decline in worth and discontinuation throughout the country. “Not worth a continental,” in reference to the national currency, was a common refrain at the time.

Amid the financial disarray, Congress ceased payments and issued “certificates,” or formalized IOUs, to the soldiers and officers of the Continental army in lieu of the compensation they had been promised for leaving their farms, shops, and families to fight the war. To supply the army, the government authorized the military “impressment” or confiscation of property—crops, livestock, and other necessities—from civilians who were also “paid” in certificates.

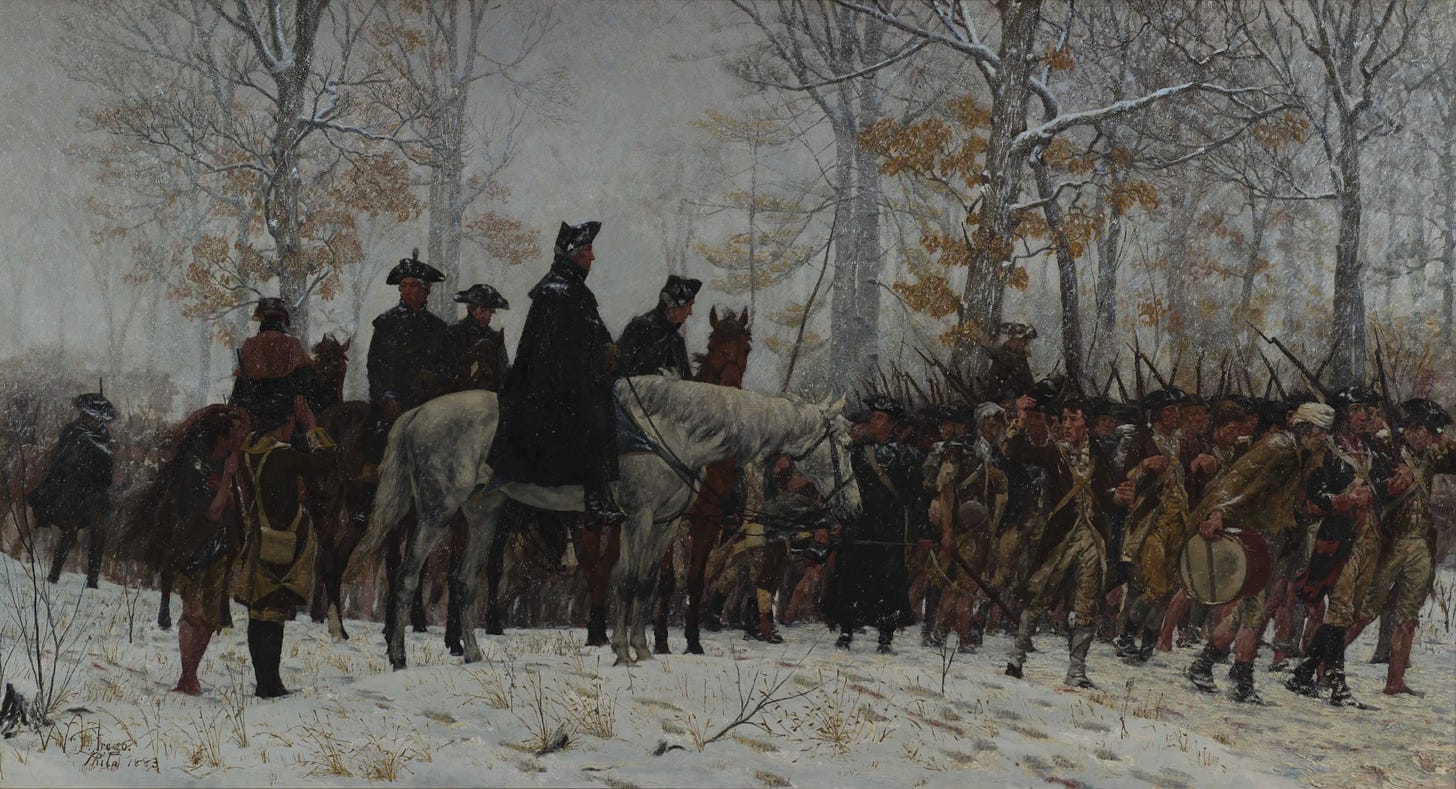

The growing sense of destitution and desperation among the unpaid soldiers erupted in a series of uprisings and mutinies at military camps in New Jersey and New York towards the end of the war, subdued only by General George Washington’s quick responses combining placation with harsh retribution, including execution of mutineers. At Newburgh, New York, in late 1782, a group of officers, due pay and pensions, sent a petition to Congress declaring “We have borne all that men can bear—our property is expended—our private resources are at an end,” and warned that “any further experiments on their patience may have fatal consequences.” Washington famously quelled the Newburgh mutiny in a personal appeal that blended personal force, principled persuasion, and a bit of stagey sentiment. In 1783, after the war was over and the army disbanded, 80 veterans assaulted the headquarters of Congress in Philadelphia to demand their pay, sending the legislators fleeing to Princeton, New Jersey.

Following the war, the majority of veterans—many of whom were disabled—the widows of war dead, and citizens whose property had been confiscated sold their “final settlement certificates” as expeditiously and for as much as they could get, which was typically 10 to 15 cents on the dollar. The sellers were mostly farmers and tradesmen, typically poor, desperate for money, despairing of ever receiving full payment, and generally ignorant of finance and national politics. The buyers were typically wealthy merchants from the big, northern cities, who bought large numbers of certificates through agents sent into the countryside, had the financial wherewithal to wait out the actions of the government in redeeming them, and were close to, or among, the insiders forging those plans. Many certificate holders were delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, a major impetus for which was to forge a stronger federal government that was capable of paying its debts. Many speculators also became members of Congress.

Although the market value of the certificates remained low through the 1780s, speculators kept gobbling them up until they were concentrated in very few hands, indicating the buyers’ confidence that the government would ultimately redeem them. Yet, this is not the message they typically conveyed to sellers, according to at least one observer. “What was the encouragement when they offered their paper for sale?” wrote one Massachusetts veteran to a local newspaper of his friends’ dealings with speculators. “That government would never be able to pay it, and that it was not worth more than 2s for 20s. This was the language of all the purchasers.”

Soon after ratification of the Constitution in 1789, which finally gave the federal government sufficient power of taxation to manage the nation’s finances, the new Congress asked Treasury Secretary Hamilton to prepare a report detailing the nation’s economic situation and his recommendations for remediating it. Presented to Congress in January 1790, Hamilton’s Report on Public Credit stated the Federal debt was about $54 million, a huge sum at the time, of which almost $12 million was due to foreign lenders. Hamilton proposed that the more than $40 million in government certificates owed to U.S. citizens be redeemed at full face value to the current owners, with a slight diminution of the promised interest.

Police and the Presumption of Ignorance

Hamilton’s debt redemption plan meant that the speculators had won their bets and the citizens who had sold their certificates, often because their unpaid wartime service and sacrifices had driven them into poverty, were out of luck. Hamilton asserted that “after the most mature reflection,” he rejected the idea of payment to the original certificate holders instead of, or along with, the speculators (current holders) because it would be “ruinous to public credit,” and, in any event, would be impractical to track down such individuals amongst all those who might have held the debt over the years. (The foremost expert on federal era finances, E. James Ferguson, has described the latter premise as false). Hamilton even vied for the high ground by arguing that certificate sellers had gotten cash expeditiously and shown little faith in the future of the republic, while the current holders had risked their money and shown belief in the government.

Hamilton biographer, Ron Chernow, argues that Hamilton was protecting the sanctity of contracts and, thus, the creditworthiness of the U.S., by showing that its government would not interfere retroactively with a financial transaction. “To establish the concept of the ‘security of transfer,’ Hamilton was willing to reward mercenary scoundrels and penalize patriotic citizens,” wrote Chernow. “With this huge gamble, Hamilton laid the foundations for America’s future financial preeminence.”

By all accounts, Hamilton scrupulously avoided conflict of interest in his office; his Treasury Department prohibited employees from dealing in public securities. Indeed, this policy marked the beginning in the U.S. of a code defining conflict of interest in public office, which was otherwise ill-defined at the time. Yet, Chernow notes that “it did not seem to occur to Hamilton … that legislators should also be beyond suspicion.” There is also evidence that prominent investors were able to infer Hamilton’s plan before it was formally announced; several weeks before Hamilton submitted his report, the market price of a dollar certificate soared from as low as 18 cents to 50 cents. One source might have been Hamilton himself through his frequent conversations with prominent investors as friends and consultants. A more likely leak, however, was Hamilton’s close confidant, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury William Duer who was a highly active and unscrupulous speculator. Duer left his Treasury post later in 1790, was later complicit in a financial scandal, and died in debtor’s prison in 1799.

The reading of Hamilton’s report in Congress sparked a fresh and unprecedented frenzy of speculation among investors who sent purchasing agents racing across the countryside. “Everywhere men with capital—and a hint—were feverishly pushing their advantage by preying on the ignorance of the poor. Thus, paper held for years by the private soldiers was coaxed from them for five, and even as low as two, shillings on the pound by speculators, including the leading members of Congress, who knew that provision for the redemption of the paper had been made,” wrote Claude G. Bowers in his 1925 history of the period, Hamilton and Jefferson.

Madison, the chief architect of the Constitution and a House representative from Virginia, watched it all with grim distaste, noting in a letter that “emissaries are still exploring the interior and distant parts of the Union in order to take advantage of the ignorance of (certificate) holders.” As a congressman in the early 1780s, Madison had argued against the general idea of “discrimination” between past and present holders of government securities as injurious to public credit, arguing that only current holders had valid claims. However, he was now convinced that the nation’s debt to the veterans was no routine financial transaction but a moral obligation.

Speaking before Congress in February 1790, Madison led the opposition to Hamilton’s plan. He reminded his peers that the value the soldiers had delivered to the nation had never been repaid; they had been forced to take IOUs that were virtually worthless on the open market or nothing. “The same degree of constraint would vitiate a transaction before man and man before any court of equity on the face of the earth,” he argued. Madison invoked the sufferings of the veterans that a just nation could never forget, contrasted with the injustice of their losing seven-eights of their compensation to others who would make a seven-fold gain based on speculation. “At present … the loss to the original holders has been immense. The injustice which has taken place has been enormous and flagrant and makes redress a great national object,” he declaimed.

Accused of allowing his heart to overrule his head, Madison replied that the issue was not an “ordinary case in law” but one demanding “great and fundamental principles of justice.” To resolve the competing claims, Madison proposed that present holders be paid at the prevailing market rates, which had risen to 50 percent of the face value, netting most of them a healthy profit. The original holders would receive the residue, or the other half of the full payment.

It was all for naught. Madison’s motion was defeated by a vote of 36-13 (nine representatives from Virginia and four from other Southern states sided with Madison), largely on grounds that it was impractical, more expensive than Hamilton’s plan, and would violate contractual integrity.

Only long afterwards was it determined that 29 of the 65 members of the House of Representatives that voted down Madison’s plan and approved Hamilton’s held certificates, according to Bowles. House members with particularly large stakes in certificates and state debts, which were be assumed by the federal government under Hamilton’s plan, included Elias Boudinot of New Jersey ($49,500), George Clymer of Pennsylvania ($12,500), Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts ($33,000), and Roger Sherman (nearly $8,000) and Jeremiah Wadsworth ($21,500) of Connecticut, according to financial historian Howard Wachtel. Wadsworth was a particularly fierce opponent of Madison’s position, reportedly exclaiming during the debate, “Poor soldiers! I am tired of hearing about the poor soldiers!” Both U.S. senators from New York, Rufus King and Philip Schuyler, Hamilton’s father-in-law, were also speculators, Schuyler holding $67,000 in certificates. For perspective on these amounts, the average total claim for a Revolutionary War veteran was $200-$300.

When Congress’ decision was announced, the general public erupted in letters to the many newspapers of the time, the “Twitterverse” of the era. “Would it not be a good regulation to oblige every member of Congress … to lay his hand on his heart and to declare that he is no speculator; and that he did not come forward to claim for himself the price of the blood or the limb or the life of the poor soldier?” wrote “A Farmer.” A “War Worn Soldier” thanked Madison for his stand against “the bloodsuckers … to boldly vindicate the rights of the widows and orphans, the original creditors, and the war worn soldier.” A “Citizen of Boston” averred that Madison and others voting with him had “probably immortalized their memories.” Among the financiers of the big cities, in contrast, Madison was the object of opprobrium. Hamilton later sneered that his erstwhile friend Madison had a poor grasp of economics.

For his part, Madison was left with grave concerns about the new republic he had helped to create. “There must be something wrong, radically and morally and politically wrong, in a system which transfers the reward from those who paid the most valuable of all considerations, to those who scarcely paid any consideration at all,” he wrote to a friend.

Historians generally agree that Congress’ approval of Hamilton’s debt redemption plan was the right thing to do for the infant nation’s economic health and growth, and its military security, which heavily relied on financial solvency. The stupendous economic success and military power of the U.S. in the following centuries would appear to validate that judgment. But the plan also had its costs, its downsides. While it may have laid the foundation for America’s future financial success, Hamilton’s “huge gamble,” and particularly the abuse of it by members of Congress, also drove a fissure in the foundation of American society.

Echoes of the debt debate of 1790 are arguably discernible throughout American history to the present day: the resentment of ordinary Americans towards financial elites; the inequality and concentration of wealth; the tax laws favoring capital gains over earned income; the rural-urban divide; the chronically poor treatment of veterans; the many violations of the 2012 STOCK act by legislators; and the alienation of the American people towards their government. A 2022 Pew poll found that 65 percent of all American adults, with equal shares in both parties, believe that all or most politicians who seek office do so to serve their own personal interests, and just 20 percent trust the government to do the right thing all or most of the time. Former President Donald J. Trump’s constant refrain that the U.S. system is “rigged” and his appeals to a sense of grievance among ordinary Americans were major themes in his political rise; his persuasion of millions of the fallacy that the 2020 presidential election had been stolen; and in fomenting an assault on the Capitol in a violent attempt to disrupt the peaceful transition of power for the first time in U.S. history.

The story of the Revolutionary War debt suggests that alienation from government among the American people has roots dating to the very founding of the U.S., with Congress deeply implicated. Hence, the proposed bans on stock trading for members of Congress, and the question of conflict of interest among lawmakers, are not minor concerns to be dismissed or delayed indefinitely but carry profound historical resonance in this country. It is long past time that Congress took steps to repair an ancient and dangerous flaw of its own making—a fracture of mistrust between the American people and their government—in the nation’s foundation.

Larry Deblinger is a freelance writer with specialties in history and healthcare.

Thank you for expanding on this piece of history. I knew the soldiers didn’t get paid but not the story of who DID get paid! Once again, an imperfect Union. Worldwide, humanwide.

Would it be alright if I post a link to this on my Post News account?