The GOP is Favored in 2022

Democrats aren’t doomed in next year’s midterms, but history is not on their side

There’s another election in two years.

It’s one of the fundamental rules of American politics—maybe the fundamental rule. Almost as soon as one election ends, attention turns to the next.

2020 was no different. Scarcely had the votes been counted and Joe Biden declared the presumptive winner that prognosticators began surveying the political landscape for 2022. A few months later, previews of the midterm appear with the regularity of subway trains at rush hour, each offering their own gloss on what the most important portents are for next November. But such exercises in divination are unnecessary.

There is one and only one omen to consider when predicting a midterm: what happened in the last presidential election. That oracle has already spoken. And it prophesied what it has so many times before: Republicans are favored to win control of one or both chambers of Congress because Joe Biden is president of the United States.

The House

There have been 40 midterm elections since 1860. The president’s (or “in”) party emerged from 37 of those with a smaller share of seats in the House of Representatives than it had going in.

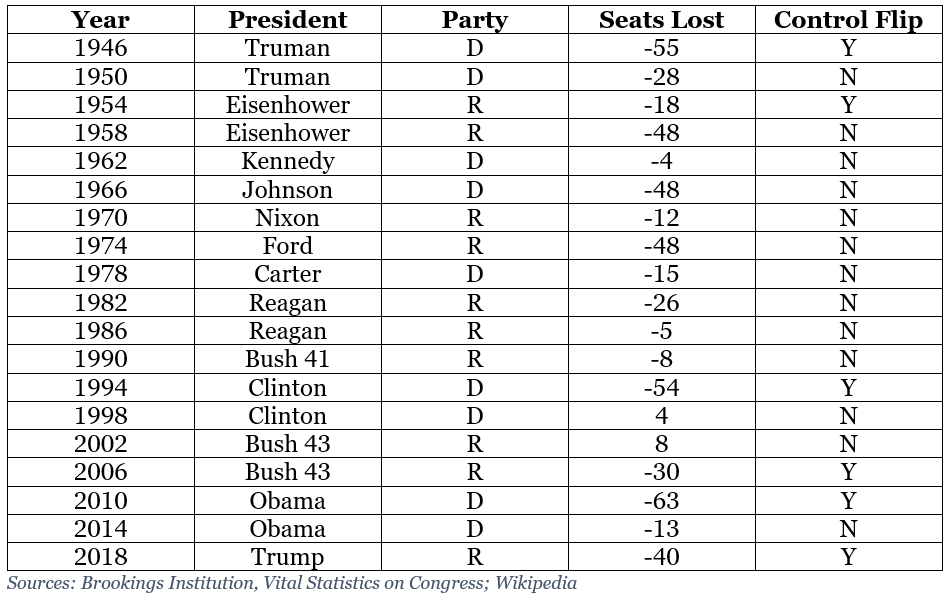

To keep this analysis manageable, I will focus on the 19 midterms since World War II. If each chamber of Congress is considered separately, there have been 38. In the next section, I will turn to the Senate. Here, I look at the House. This simplified chart shows the midterm results in the House since 1946.

A party needs 218 seats in the House for a majority. In last November’s election, Democrats won 222 to Republicans’ 213. To regain control, therefore, the GOP needs a net pickup of only five seats. As you can see from the table, a loss of five seats is on the low end for the president’s party, which has lost on average about 26 seats in post-war midterms.

To keep the House, Nancy Pelosi and co. would need to match the lowest number of seats lost by the in party in a midterm, four in 1962. The next four lowest totals—five, eight, 12, and 15—would give the House to the GOP. Even a result 50 percent worse than average for Republicans, in other words, would flip the House.

Democrats find themselves in such a precarious position because Republicans made a surprisingly strong showing in the House last fall. Forecasters expected them to lose 10 to 15 seats, putting Democrats close to 250 in the most optimistic scenario. Instead, defying expectations as they did up and down the ballot on November 3, Republicans won 14 seats, while Democrats were reduced to their smallest majority in decades.

Compounding Democrats’ peril, they failed to win a single state legislature, leaving Republicans with a decisive advantage when it comes to redrawing congressional districts as required every 10 years after the census. Their triumph in the 2010 midterm allowed Republicans to draw many maps favorable to them afterwards and they are poised to do so again.

Not only will Republicans have the upper hand on redistricting, they will get an added boost from reapportionment, as states whose populations declined over the previous decade lose seats and states whose populations rose gain them. The states losing seats are “blue” states like New York, Illinois, and Pennsylvania, while “red” states such as Florida and Texas will receive multiple seats each. As RealClearPolitics’ Sean Trende concluded, “reapportionment and redistricting alone will likely cost Democrats their majority.” That’s before any other factors are taken into account. If this is correct, the Democrats will surrender their majority long before a single vote is cast.

Even a historically good performance where they only lost a dozen seats wouldn’t be enough to save the majority. There are two exceptions to this pattern: in 1998 and 2002, the president’s party gained seats. But both elections had extenuating circumstances. In 1998, Bill Clinton had a 60 percent approval rating and voters punished Republicans for impeaching him over a sex scandal. And 2002 was shrouded by the smoke still rising from 9/11.

Bleak, dire, grim—choose the descriptor you want, when it comes to the House, things look bad for Team Donkey. The House, though, is only half of Congress. It is not Democrats’ last hope; there is another—the Senate, where things do look better for them. But that doesn’t mean they look good.

The Senate

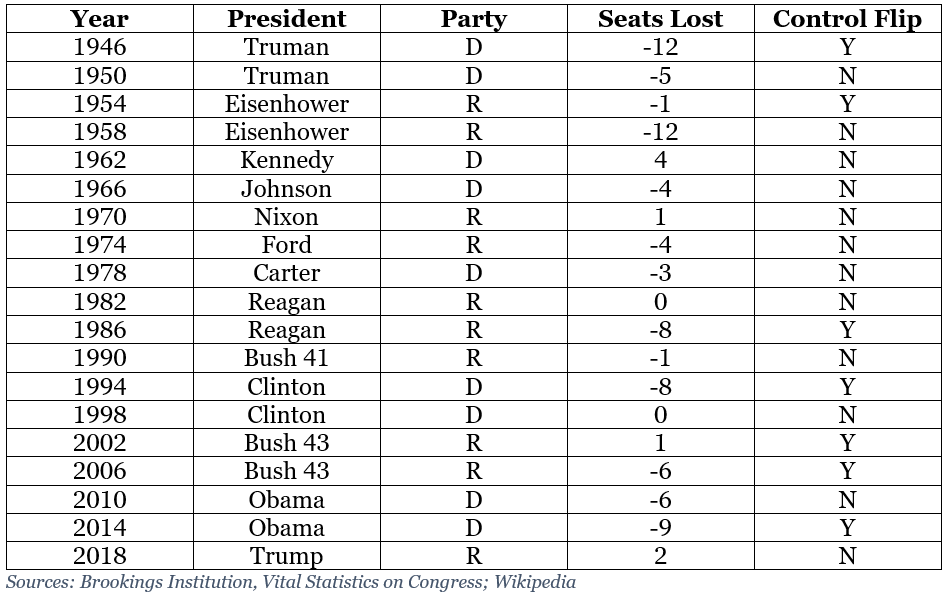

The president’s party fares badly in the Senate in midterm elections, but as the following table shows, not quite as badly as in the House.

In the Senate as in the House, equaling the best showing for the in party when it lost seats in a midterm (one by the GOP in 1990) would still cost Democrats the majority because it is currently divided 50-50. That holds if they match the next three “best” performances: two in 1954 and 1978, three in 1966, and four in 1974.

The good news for Chuck Schumer and co. is that since World War II, the in party has broken even or gained ground in the Senate in six out of 19 midterms. That works out to just under a third of the time, a much better record than the paltry two of 19 in the House. Just as the loss of a solitary seat would flip the chamber to the Republicans, a gain of one would give Democrats 51 seats and spare them from relying on Kamala Harris’s tie-breaking vote. History says they have a one-in-three chance of doing just that—odds they would no doubt take.

Best of all from Democrats’ perspective, the Senate map favors them. They will be defending 14 seats, mostly in friendly territory. Republicans, on the other hand, have to defend 20 seats, including two in states Joe Biden won, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Even worse, they’ll have to protect some of these seats without the advantage of incumbency. Several GOP senators have already announced their retirement, including Pennsylvania’s Pat Toomey. Wisconsin’s Ron Johnson is undecided about seeking a third term.

Although most open seats won’t be in danger, GOP retirements in Ohio, Missouri, North Carolina, and (potentially) Iowa could put them into play depending on the national environment and the quality of the Republican nominee. Marred by scandal as he is, disgraced former Missouri governor Eric Greitens would be favored to retain the seat of the departing Roy Blunt. But it’s a risk GOP leaders assuredly don’t want to take. No more do they wish to be saddled with a MAGA diehard who is poison in the Philadelphia suburbs.

Democrats do possess a few competitive seats, such as Nevada, New Hampshire, and the two former Republican strongholds which swung to Joe Biden, Arizona and Georgia. Even if they held all their seats, Republicans would still need to win one of these to get the majority. Their best shot is New Hampshire, where polling indicates the popular GOP governor, Chris Sununu, would be a strong challenger to Maggie Hassan, who won by a mere thousand votes in 2016. Depending on how things shake out, it might be their only shot.

As Trende explained, “Democrats simply don’t have much exposure this election.” They have no seats in states Donald Trump won, and they have to defend fewer seats overall than the GOP. This isn’t to say they’re favored; they aren’t. The president’s party loses on average two to three seats in a first midterm. A one-in-three chance still means the odds are against them. But they’re better than the miserable odds in the House.

Midterm Madness

History says the Democrats are screwed. But history doesn’t vote. If Democrats lose one or both houses next year, it won’t be because of what happened in 1862 or 1926 or 1994 or 2010. It’ll be because of what happened in 2021 and 2022. Every election is a discrete event shaped by a unique set of circumstances.

And the circumstances operating over the next two years are likely to be so uniquely favorable to the Democrats that they will break the midterm curse. So contend several progressive commentators who believe Joe Biden will do to history what he did to Donald Trump.

The argument that history will be irrelevant to the outcome of next year’s midterm has been articulated most forcefully by the election forecaster Evan Scrimshaw. History is bunk, he avers, because polarization means voters no longer pick either party equally. The midterm penalty for the in party existed because someone who voted Democratic for president was as willing to vote Republican two years later, and vice versa. That is no longer the case. Affluent, college-educated voters now lean to the left while downscale voters have shifted to the right. Scrimshaw posits that this is a bad trade for Republicans because the former are regular voters but the latter aren’t. “If your electoral success is based on low propensity voters, then you're in a lot of trouble when they don’t turn out.” Infrequent white voters down the economic ladder turned out for Trump in 2016 and 2020, but not Republicans in 2018.

For Democrats to suffer the typical midterm losses next year would require “a high number of swing voters, suburban reversion, or Hispanic non-reversion.” Scrimshaw dismisses all three, and thereby dismisses the midterm penalty not only from next year’s election but from American politics. “The Midterm Penalty was a very real thing for a very long time, a real part of American politics that explains a lot of the past. But what it isn’t is meaningful moving forward.”

Is he right? Maybe. We don’t know. It’s never happened before. It’s a prediction (and Scrimshaw’s record is charitably described as mediocre). But when you predict something will happen that has never happened before, you can’t offer any proof or evidence because none exist. The reason people expect the Democrats to lose next year is because that’s what the president’s party has been doing in midterms, with a few exceptions, for the last century and a half.

It’s possible that next year, for the first time, changing electoral coalitions, demographic shifts, and the economy will be factors in the midterm. But they haven’t been before. The economy certainly didn’t help Trump in 2018. Just as it never helped his predecessors. Demographics have been changing, electoral coalitions have been shifting, for the last 150 years. And all along the president’s party has been losing seats in Congress in midterms. The midterm penalty is a secular trend which operates beyond economics, demographics, voting patterns, etc. 37/40 isn’t a historical contingency, it’s a structural feature of American politics.

The argument for why next time could be different is literally that next time could be different; or to use a popular internet jibe, “because reasons.” Which it could be. But anyone making that claim must offer a better justification than insisting that things which have never been a factor in midterms before are suddenly going to be now, just in time to help Joe Biden (and, coincidentally, validate their partisan commitments). Next time could be different. But as of now, there’s scant reason to think so.

To understand why, let’s turn to the strongest case for “how Democrats can break the midterms curse,” elucidated by The Economist’s election analyst, G. Elliott Morris. What quickly becomes apparent from his assessment is that even the strongest case is a weak one. For one thing, as he explains, even 5 percent growth in real incomes a year before the election translates into a loss of 10 seats in the House.

For another, the statistic that has the most bearing on midterm performance, presidential job approval, bodes ill for Democrats. To gain seats in the House, a president’s standing has to be at 68 percent or higher. Biden’s numbers are good, but not that good. “If Biden can improve his approval rating to 60 percent, which will be hard but is not entirely out of the question, the Democrats might be able to survive in the House.” That even 60 percent may not be good enough shows you how daunting their task is.

On his present trajectory, the president is unlikely to get there. His rating stands at a respectable 53 percent approval, 40 percent disapproval in the FiveThirtyEight average. In live-caller polls (which, admittedly, may no longer be the gold standard they once were), Biden’s position is fairly pedestrian for a president just at the end of his honeymoon period. He had a net positive rating in the latest polls from CNBC and Quinnipiac, but he was under 50 percent in both at 47-41 and 48-42, respectively. Those are, frankly, lousy numbers. He fared better in surveys from Monmouth (53-43) and NPR/Marist (52-41). That’s higher than Trump, but worse than every other recent president. Moreover, as Morris pointed out on Twitter, there’s reason to believe that polls are currently overrating Biden just as they did leading up to the election. As a president’s approval tends to erode as his tenure goes on, Biden’s positive marks today are unlikely to be much solace to Democrats two Novembers from now.

Republicans’ big advantage is that they have so little ground to make up. They don’t need a historic midterm like 1994, 2006, or 2010 to win the House. Something modest like 1990 would do the trick. The wave elections of recent years have warped our perceptions. If Republicans take the House in 2022, that would make four of the last five midterms in which it changed hands, with 2014 the only exception. Because of this, we forget that even when the Democrats had huge majorities in the House and controlled it for four decades from 1955-1995, the president’s party still lost lots of seats. Losing seats and flipping the House aren’t the same.

If Democrats had gained the 10-15 seats last year forecasters projected, thinking they’d hold on next year wouldn’t have been unreasonable. That would have given them 245-250 seats, a number that might have put the House out of reach. Then, even if Republicans won the average number of seats for the out party in a post-war midterm, they’d still come up just short.

They might anyway. Perhaps the memory of Donald Trump will make the GOP toxic to voters. Or maybe his influence leads to the nomination of a new rogues’ gallery of unelectable candidates like those who cost the party several Senate seats in 2010. The post-pandemic recovery could be so magnificent that the economy erases all other considerations and Democrats benefit from an unprecedented midterm wave in favor of the president’s party. And possibly Nate Silver is right and “the calculation is a lot different” this time because voters will suddenly start thinking like no one does who isn’t on Twitter when confronted with the prospect that “the minority party could use a good midterm to permanently entrench itself.”

The only way to lose a seat is to win it first. In this sense, losing is a sign of success. Democrats were successful last November, which is why they’re on the verge of losing control of Congress next November. But holding on, though a remote possibility, isn’t out of the question. Twice out of 19 midterms the president’s party has gained seats in the House. Six out of 19 it has lost none or won them in the Senate. That adds up to eight out of 38 elections, or just over 20 percent. Not the best odds, but not zero, either. And if nothing else, both chambers of Congress haven’t flipped in a first midterm since 1994.

Democrats are likely at their high point of the cycle right now. From here on out, the president’s approval declines and his party falls on the generic ballot. Extrapolating from historical trends, CNN’s psephologist Harry Enten calculated that based on present polling, Republicans will win by four or five points. It would, therefore, “take a historical anomaly for Republicans not to gain ground in the midterms.” No wonder some pundits are so eager to cancel history.

Simply because of the way midterms work—that is, as a referendum on the president—the Republican Party should be expected to gain seats in one or both chambers of Congress in 2022. Anyone who argues otherwise is wrong as a matter of fact and history. Which isn’t to say Democrats can’t beat the odds. It’s just that beating the odds may in the end not be enough.

Nicely done. The two recent midterms in which the president's party didn't lose House seats had, say, extenuating circumstances. In '98, Clinton beat back the GOP's ham-handed attempt to remove him from office. Voters made the GOP pay.

In 2002, GWB was still enjoying strong support for his work post-9/11 and the Iraq War hadn't yet started.

As you mention, if there's a strong economic recovery under way, Biden probably will get credit for it; moreover, if Republicans are stuck on running MTG/Gaetz/Boebert types, non-crazy Democrats could pick up seats as well.