This is What Happens When You Find a Stranger in the Alps!

Patrick Deneen’s new book, Regime Change, may be shallow and unoriginal, but at least he expresses his reactionary opinions politely

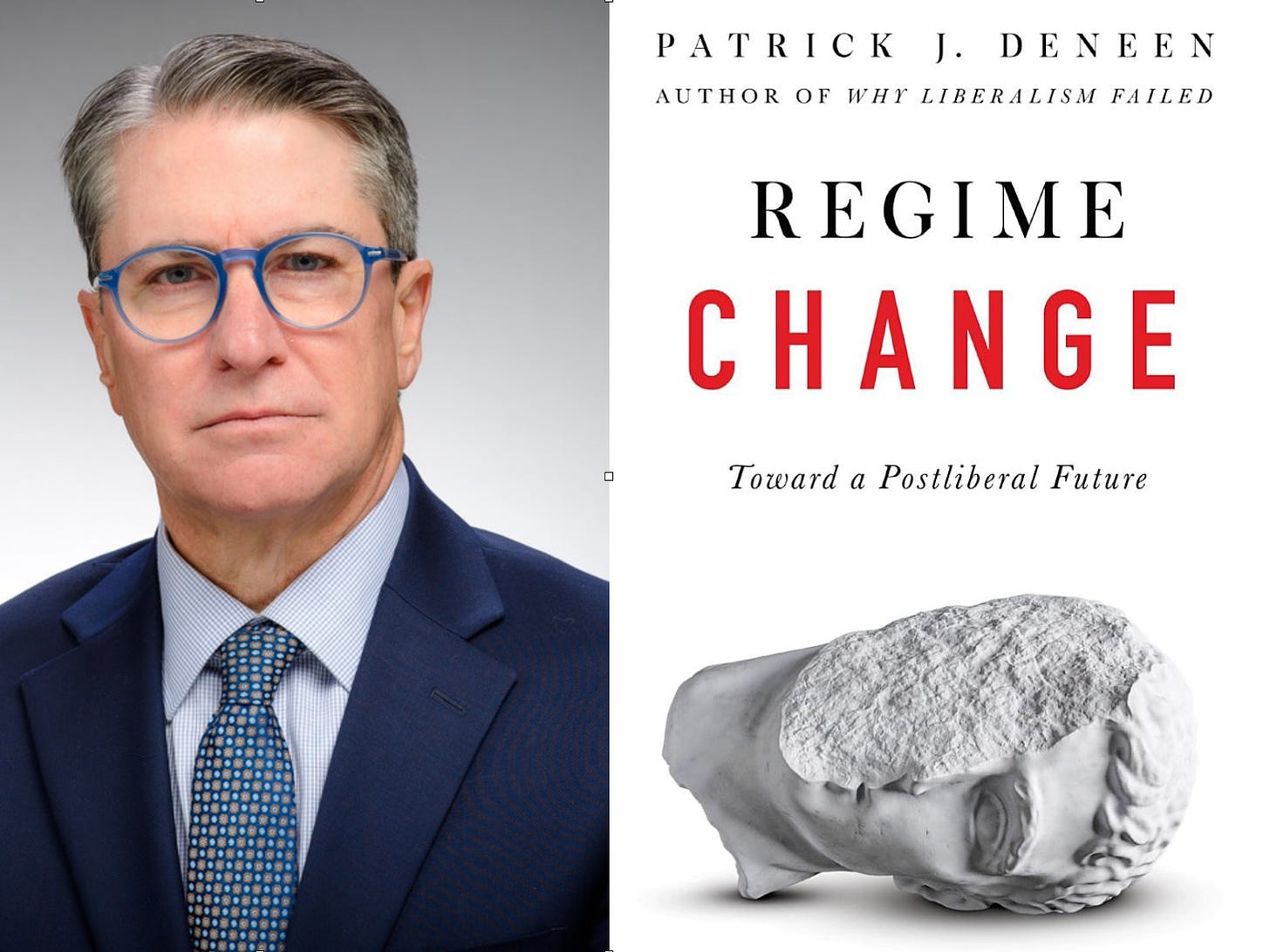

Regime Change: Toward a Postliberal Future

Patrick Deneen

Sentinel, 288 pages, 2023

The decades around 3200 BC were a momentous time for southern Mesopotamia and for world history. The population of the city of Uruk, in what is now southern Iraq, had swelled in the previous centuries to perhaps 50,000 people within the city walls and maybe twice that in the immediate countryside—an unprecedented size. The temple complexes devoted to Anu and Inanna had recently undergone major construction and reconstruction projects. There were Urukian “colonies” up the Tigris and Euphrates as far as away southern Turkey, and to the east on the Iranian plateau. More fatefully, writing was invented as an improvement to the “token” system that had been used for millennia to track the production of grain and wool. Within a century or so of this cultural ferment, the Uruk “world system” was in retreat: most of the “colonies” were abandoned and the large temples in Uruk were razed; the practice of writing persisted, but its development stalled. Life around the city appears to have continued, but it would be centuries yet before the energetic culture of the Dynastic Period, captured in the Epic of Gilgamesh, would come into focus.

In his new book, Regime Change, Patrick Deneen laments for a “world system” that, according to his narrative, has been lost. Picking up from his previous book, Why Liberalism Failed, he argues that the regime governing “The West” needs to be replaced and he offers a snapshot of what its replacement might look like. While not adverse to discussing other countries, both historically and in the present, the focus is not really “The West,” but the American system. The book is framed in reactionary vogue: that secularization makes society decadent and degenerate; that the attrition of “traditional” social roles and cultural practices saps meaning from life; that various flavors of “leftist” ideology are responsible for an equally various array of institutional failures; that a reinvigorated and politicized Christianity is the key to rescuing our decaying culture.

However, his analysis takes an interesting tack. He contends that these problems are largely a function of class conflict, where there are two fundamental classes, the “few” and the “many.” The “few” are the managerial class that constitute a “ruling elite,” and would seem to resemble Marx’s capitalist bourgeoisie. The “many” are the “working class,” a multi-racial volk who, being less sophisticated and more attached to local, “conservative” sensibilities, have been left behind by industrialization. Liberalism is the ideology of the “elite” and it is predicated on a notion of unending “progress.” Nominally, this would entail a persistent effort at technological innovation, the growth of material production, and the scaling up of a globalized economy that erases local cultural difference; but, at a deeper level, “progress” is not aimed at sundry improvements to our material condition or socio-political integration—it intends rather to engineer a new social order through a permanent revolution of the political economy. In Deneen’s view, what liberals have engineered instead is a society who has lost its soul.

The “liberal elites,” therefore, have produced the cultural catastrophe whose traumas reactionary intellectuals so often litanize. He says at the end of the first chapter (p. 25):

While both classes are responsible for this cycle, the ruling class bears the most responsibility, having the most resources. Unfortunately, the current ruling class is uniquely ill equipped for reform, having become one of the worst of its kind produced in history…

Deneen admits that liberalism has been extraordinarily successful in its program; it’s just that its success has imposed tremendous cultural costs on industrialized societies, and he believes that these costs could have been avoided in a counterfactual history where liberalism failed to take root. To counteract liberalism’s disintegration of “The West,” he proposes that a new elite regime replace the “liberal elites” who have failed the common people. He calls this new approach to conservatism, “aristopopulism.”

In a recent profile of Deneen in Politico, he declares provocatively: “I don’t want to violently overthrow the government. I want something far more revolutionary than that.” While he doesn’t spell out what could happen if this new regime doesn’t coalesce, it is easy to surmise, out of the eschatological thinking common among the reactionary set, assorted grim predictions.

One can imagine some distinguished man at the time spinning a tale where the collapse of the Late Uruk system constituted the disintegration of a civilization that had been developing vigorously during the preceding millennium. This fellow might have excoriated the political elites of Uruk and demanded a return to past ways, lest the sacred culture be forever lost. Except that when Alexander died in 323 BC, almost 3000 years later, he died in Babylon, still, then, the center of the ancient world, many of the core Urukian cultural features yet intact, having been maintained continuously over the triumphs and catastrophes of thousands of years.

Aristotle, in the Conservatory, With a Crucifix?

Deneen begins his book by briefly citing well-known social problems, such as the opioid crisis, declines in family formation, and public talk about civil war. While he mentions environmental problems and economic issues later in the book, he seems mainly concerned with social ills of a spiritual nature, where some sense of meaning in life has been absented. He makes no hint that these issues may have complex causes or ambiguous social consequences: he draws a straight line between such cataclysms and liberalism as an ideology embodied by the “liberal elite.” Perhaps he explored these complexities in his previous book (I’ve decided to review this book on its own terms); here, he takes liberalism’s “failure” as an article of faith.

The book’s worries about the ideology of “progress” are not merely conceptual, but structural. We like to think of America as a “meritocracy” where talent and hard work are rewarded by institutions with money, prestige, and power. Deneen feels this works against the “many” in two ways. First, it prioritizes skills involving symbol-manipulation, rather than physical or other kinds of skills, and so it actively devalues the types of jobs most accessible to the “working class.” Second, the “merit” part of “meritocracy” is something of a shell game, where education and social connections mean more than raw talent and a willingness to work hard. This divergence in outcomes along class lines translates into a geographic asymmetry where cosmopolitan, urban locales are centers of the services economy of benefit to the “elite,” while the rural hinterland molders and falls apart. Cities are the locus of a globalized culture where any city is as good as another as long it makes money for urban professionals and has the usual trendy accoutrements; they encourage in the lives of their residents detachment and uniformity. In the countryside, rootedness and localized customs are honored, and this fosters a grounded outlook that prefers common sense over the latest intellectual fashion.

While he spends some time extolling the probity of the “working class,” the book is much more concerned with attacking “liberal elites.” Occasionally, his punches land (p.8):

Today, the essence of elite formation consists of two main objects, irrespective of major or course of study: first, taking part in the disassembling of traditional guardrails through a self-serving redefinition of those remnants as systems of oppression; and second, learning the skills to navigate a world without any guardrails. College—especially at selective institutions—is a place and time in which one experiments in a safe atmosphere where guardrails have been removed, but safety nets have been installed. One learns how to engage in “safe sex,” reactional alcohol and drug use, transgressive identities, cultural self-loathing, how to ostensibly flaunt traditional institutions without bucking the system—all preparatory to a life lived in a few global cities in which the “culture” comes to mean expensive and exclusive consumption goods, and not the shaping environment that governs the ambitious and settled alike. Those outside these institutions also have had the guardrails removed—all are to be equally “free”—but without the safety nets in sight.

Interestingly, he emphasizes that Reaganite “conservatives” are actually liberal in the “classical” sense of the word—meaning that much of the politics of the pre-Trump era in the U.S. was an intramural conflict among liberals. Yes, these “classical liberals” have preferred a slower pace of social change, but they have supported many aspects of the liberal program, such as globalization, an aggressively internationalist foreign policy, permissive immigration laws, free markets, and a willingness to embrace new social norms on matters like no-fault divorce, gay marriage, and even abortion. Contending with this “classical liberalism” is a left-leaning variety, which is what we usually label as “liberal,” and this he calls “progressive liberalism.” In contemporary America, this is basically the Democratic Party and its registered constituents.

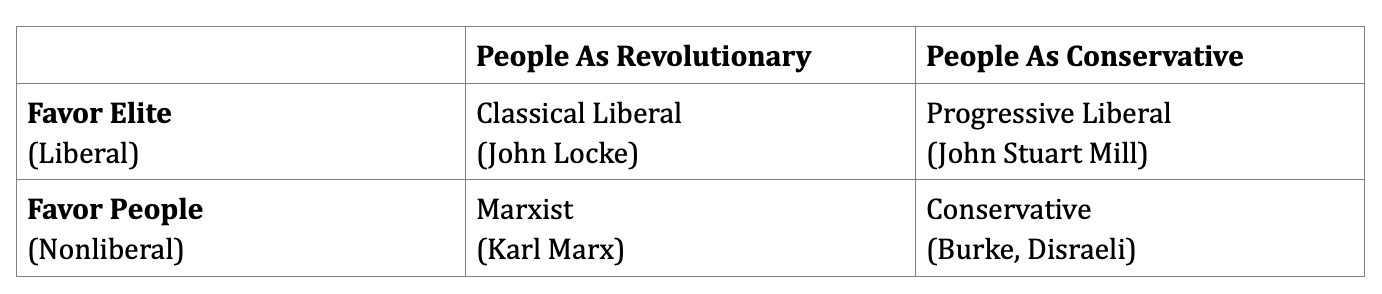

Deneen puts forward a scheme that includes these two varieties, as well as Marxism and the “conservatism” of his aristopopulist program. He has a nifty little matrix based on two oppositions: A) the “many” as revolutionary versus the “many” as conservative; B) a “liberal” bias towards the “few” versus a “nonliberal” bias towards the “many.” He cites iconic intellectuals for each box in the square (p. 91):

In this telling, “liberalism” in social conflicts sides with the managerial class, as an elite, ruling class, against the throng of working folk. The difference between Reaganesque “classical liberals” and the “progressive liberals” is their characterization of the attitudes of the working class. Are the volk a force for revolution: in which case they need to be put in their place, lest they try to seize power? Or, are they essentially conservative in outlook: in which case they need to be induced by public give-aways and culture war fodder to participate in the ideology of “progress?” On the nonliberal side of the ledger, the Marxists see the “people” as a revolutionary force, and want to encourage their taking of power, rather than suppress it. Deneen’s critique of Marxism is not that the solicitude for the working class is wrong, but that the “people” are actually conservative, and therefore Communist societies have inevitably ended with an entrenched elite of political insiders who abandon their ideals when they become disillusioned by the conservativism of the unwashed masses they had believed or pretended they were attempting to uplift.

Out of these four possibilities, Deneen can only allow “conservatism” as a good way to constitute a society. In his account of “conservatism,” the elite should labor to benefit the working class, not by fomenting revolution on their behalf, but by reinforcing their traditionalism. The “conservative” ideology should value stability, order, continuity, safety, certainty, and it is the responsibility of elites, through cultural products, moral norms, and public policy to provide guidance for the lower orders, such that they follow their inherent inclinations.

His conception of the “people” is oddly passive, and, frankly, incompatible with the American can-doism that has long been noted as a core feature of the country’s character. The “many” are, apparently, unable to form meaning in their lives or adhere to healthy behavioral norms without social conventions enforced by elites and paternalistic policy-making. He says he abhors violence, and so Marxism’s bloody history would seem to be proof of its false conception of the working class. On the hand, he indicts liberalism (p. 146), “not because of its oppressiveness and cruelty, but precisely because of its separation and indifference.”

His solution to all of this is to seek a “mixed constitution.” He appears to mean a “constitution” in the British sense of there being traditional practices and norms within institutions governing the behavior of those operating within it, not a written document of the mechanisms of government. A “mixed constitution” means that the prerogatives of each class are blended together into a harmonious whole. Deneen’s idea of blending is not the “salad” model, where disparate behaviors and bills are tumbled together and then tossed into a pleasing concoction; what comes to mind are various class elements chucked into a food processor and whirred into some hyper-class smoothie. He believes this approach to institution building will create a “common good”—where people of all orders can flourish within what he believes are their natural proclivities.

However, the process for achieving this “mixed constitution” comes across as counterintuitive, if not directly contradictory to the ideals and ends he articulates otherwise. He claims (p. 147):

The prospects for a renewal of culture, the ascendancy of common sense, and a reimagined form of a mixed constitution rest upon the success of a confrontational stance of the people towards the elites—namely, the effort to force the vanguards of progress to work instead on behalf of the aims of ordinary people in preserving stability and continuity. In order to conserve a social order, there must first be a fundamental upheaval of its current revolutionary form.

We rendezvous here with the reactionary moment: a revolution within the revolution.

It is the role of the new aristoi to lead this confrontation, and they need not seek to achieve their ends through a neutral institutional process, but by a will to power, where the will, nevertheless, seeks this “common good.” Surprisingly, he denigrates Donald Trump, describing him as a “deeply flawed narcissist,” but he approvingly cites Viktor Orbán’s Hungary as a model for this new populist conservatism, if we have any questions about how all this is supposed to work.

While he clearly has specific Christian values and predilections in mind, the statist bent of this program may be its most protuberant quality. He says (emphasis Deneen’s) (p. 167):

Machiavellian means to achieve Aristotelian ends—the use of powerful political resistance by the populace against the natural advantages of the elite to create a mixed constitution not ultimately of the sort imagined by Machiavelli, but in which genuine common good is the result.

Machiavelli and Aristotle aren’t the right touchpoints for what he is proposing. What’s remarkable about this book is how Marxist it is. As a replacement to liberalism, Deneen tenders a new Communism—just without the lefty vibe.

Benjamin Disraeli, in the Kitchen, With a Spork?

One has to give credit to Deneen for crafting a coherent program, and for writing well. However, if one is to take his ideas seriously as theories, which would assume his book is a sincere attempt at describing reality, there are some major problems that need to be addressed.

His analysis of class is simplistic. He posits that there are just two classes, the “few” and the “many.” He explicitly identifies the “few” as the “managerial class” who constitute a “ruling elite,” a phrase which calls to mind a small group of people with immense power over a whole country or region. According to an estimate in 2022 by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics there were 9,860,740 Americans employed in “management occupations” out of 147,886,000 workers. This doesn’t include the people involved in other professional industries generally requiring higher education, 47,843,370 workers in “business and financial operations occupations,” “computer and mathematical occupations,” “architecture and engineering occupations,” “legal occupations,” “education and library occupations,” “healthcare practitioners and technical occupations,” and “arts, design, entertainment, sports and media occupations.” This is a crude division of the country’s workers, but it includes about 1/3 of the whole U.S. workforce. All of these people are not involved in “ruling” the country, even where many of them share a “liberal” political orientation. And the U.S. is not unique among developed countries in these occupational proportions.

Presumably social conflicts along other axes, such as he imagines will happen between the “liberal elite” and his hoped-for aristoi, can only take place within these two major class groupings. But this glosses over considerable differences throughout the population in income, ethnicity, immigration status, region, language, sexual orientation, age, education level, personal disposition. To his credit, he does devote a whole section to castigating racism, but he assumes that differences in race are not germane to differences in class. An exhaustive treatment of “class” would need more than two categories. This is not because modernity has “fragmented” our social structure in some unprecedented way—even Medieval Europe, Deneen’s seeming benchmark for class harmony, had much more class complexity than this, with a florilegium of royals, courtiers, magnates, knights, yeomen, merchants, craftsmen, bishops, clerics, monks, flunkies, servants, rough boys, serfs, and outsider groups, like Gypsies and Jews. His descriptions of contemporary class structure misrepresent how large and varied the U.S. is, much less everywhere else in the industrialized world, and every post-tribal society in the past.

If his idea is to describe how certain class dynamics give rise to corresponding ideological commitments, then there is something to the approach, but, by abstracting to just two rudimentary categories, what follows has severe constraints as a sociological model, which he does not acknowledge. It almost feels as though Deneen doesn’t spend much time with real people, and imagines his fellow beings as androids whose voice boxes continuously spew obnoxious culture war tweets.

Klaus Fuchs, in the Billiard Room, With the Taxidermied Remains of the Family’s Beloved Cat, Whiskers?

His model of society and all its disparate parts is not well defined. “Disintegration” is a major theme throughout Regime Change, and he appears very certain that secularism, by maintaining clean lines of demarcation among different aspects of society, has brought about a shattering of the ties that hold people together. There is a bisecting of the “few” and the “many.” There is a separation of church and state. An atomization of the individual or the nuclear family from the community. An extensive division of labor. A conflict between economic ends and spiritual ones. An incongruity of science and faith. Etc.

His goal is for culture to find a better “integration” of these disparate parts, by which he seems to mean that every social sphere of activity should be involved in every other sphere. There should be laws to regulate religious practice; religious ideas should inform human knowledge; the conclusions that are thus formed should dictate political behaviors; politics should guide economic management; the class structures that result from the economy should be codified into law.

This misunderstands the way that “integration” operates as a concept. In a developmental model, a system has to differentiate its various parts BEFORE these parts can be integrated into a whole. Without a process of differentiation, there is nothing to integrate, just a chaotic, confusing blob of no fixed form. This “separation” of different aspects of culture into each its own self-contained sphere of activity has been a process of differentiation, not of “disintegration,” and it has been brought about the transformation of agrarian societies into industrial ones. Liberalism, insofar as it is an ideology rather than a set of concrete economic structures, is a result of industrialization, not its prime mover.

Perhaps Deneen would disagree with this claim. That cultures develop is self-evident to anyone who studies history. Moreover, we live in a moment when the environment of the earth is rapidly changing, largely due to industrial activity. He mentions environmental problems a few times throughout the text, but has nothing to say about how his postliberal order will react when the conditions for a future economy have dramatically degraded, or what we can do now to mitigate bad outcomes. What is Deneen’s theory of social adaption? How should it be applied to modernity?

Whatever his ideas about this may be, he clearly wants to order his worldview on something deeper than political institutions. He says (p. 188), “…the alternative to a liberal order rests far less on systemic political arrangements, and more on a different way of understanding the human creature in relation to other humans and with the world and cosmos.” He seems to have a view that there is a preferred ideology of human meaning and purpose, and this is what should determine cultural form, something he conceives as static and fixed, not changing or developing.

Liberal order or not, he is right to believe we can better understand our place in the world and the order of the cosmos. All of our current systems of knowledge have major gaps and flaws. But reordering the foundations of contemporary human knowledge is a monumental task. It requires, first, getting a handle on what we have learned about the world heretofore—including the lessons of science and the “liberal order.”

And, then, coming up with original, technical approaches to basic questions: What is his solution for the hard problem of consciousness? What is information? What is the purpose of “poetic” or “artistic” or “mythic” representations of reality? Why do the processes of “living” things appear to differ from “non-living” things? What sets humans apart from other living organisms? What is the purpose of these different aspects of society? How does time work? How does rhythm work? What is the relation between form and function? Are the “laws” of physics static, and where do they come from, and how are they formed? Is the universe, bounded in space and time, fated to heat death? Why is there something rather than nothing?

On the basis of this book, it is safe to assume that Deneen has nothing new to contribute to such topics.

Indira Gandhi, in the Ballroom, With a Nuclear Warhead?

Deneen studiously ignores cultures and histories outside Western Europe and the United States, other than a few cursory references to the Greco-Roman world. His theories about the “mixed constitution” and the “common good” and so forth are presented as culturally and historically neutral—his style of argument is abstract, and one expects that his version of a good society is the universal one. Sometimes, however, his cultural partisanship pokes through. At one point late in the book, he declares (p. 182), “Most importantly, aristopopulism will advance in the Western nations through forthright acknowledgement and renewal of the Christian roots of our civilization.”

The moods and opinions of the lower classes in other cultures often do not accord with the “Christian roots” of Deneen’s imagining. The disconnect gets worse if we look not just at contemporary societies in Asia and Africa, but in the past too. There happens to be a field of study called Anthropology in which a dazzling array of widely divergent cultural practices have been attested over time. If his theory is supposed to be a culturally neutral one, in other words, and he believes he has stumbled upon a “conservative” account of a “good” society, he has to account for any such differences extensively and cite examples. Worse, much of the world experienced the European colonial project from the 16th to the 20th centuries as a profound cultural disaster.

He also assumes, without comment, that the American experience is fundamentally “Western.” While it is popular to use this term to describe NATO countries, we’ve discovered in recent years, particularly since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, that “Western” sensibilities seem to also encompass other democratic, highly industrialized countries like Japan and South Korea. In other words, it could be that this term is a shorthand for NATO (possibly with Australia and New Zealand added at the margins), or maybe it’s a shorthand for industrial societies that have opted for democratic governance. In any case, it is disputable whether or not America is intrinsically “Western” or “Christian.”

Even if we confine ourselves to the history of nominally Christian European countries, one wonders what slaves and serfs might have thought about the righteousness of their own “mixed constitution.” In the Americas, in particular, historical accounts of the slave experience were unrelentingly bleak. There is abundant bloodshed and exploitation documented throughout Christian societies in all periods and places before the scourge of modernity.

He extols the nobility of tradition, and this is supposed to connect the new regime to the good things from the past which liberalism has sundered. But what tradition, at what time, in what place, according to whom?

He appears not to have spared a thought about any of this.

Joan of Arc, in the Hall, With a Sex Tape?

What mechanisms does Deneen imagine will lead to the emergence of a new political and cultural regime? He proposes some policy ideas towards the end of the book:

The U.S. House of Representative should be expanded to 6,000 (!) members.

Primary elections should be replaced by caucuses.

Government departments should be moved out of the Washington DC area and be more geographically dispersed throughout the country.

Illegal immigration should be restricted by targeting employers.

Pornography should be highly controlled or banned.

The government should promote better observance of Christian holidays.

He lists other proposals, but none are suggested with much detail, or critical thought about what could go wrong. He pointedly ignores contrary evidence or inconvenient facts. For example, he assumes that immigrants take jobs from native residents, which is by no means a consensus view, especially after almost two years of headlines about worker shortages. He calls for a new era of robust industrial policy, while failing to mention the trifecta of “infrastructure” bills passed last year by the Biden Administration and a Democratic Congress.

Ultimately, the benefits and costs of such measures are debatable. But this mix of policy proposals is paltry. How is this going to turn over the entire “elite” for a country the size of America? All of this talk about a “mixed constitution” and so forth ends as mostly an exercise in abstraction. One suspects that Deneen’s ultimate aim is to express his own status anxiety, being an “outsider” who has nevertheless spent his entire professional career cloistered in the hallways of prestigious universities.

All of this is in service to an indefinite “common good.” The references to stability, continuity, order, family, etc., are also abstractions, easy to peddle as platitudes. Everything gets difficult when you start talking about specifics. For instance, the “popular” position on abortion in the U.S. is that it should be generally legal with restrictions on abortions at some point in the second half of pregnancy. While he doesn’t address abortion directly, it’s hard to imagine Deneen endorsing the objectively popular position on abortion law. This is a man who seems uncomfortable with no-fault divorce!

There are many contentious issues in American society where large blocks of people have conflicting values, preferences, attitudes, objectives, opinions. So, who gets to decide? What is the mechanism for mediating conflict? Liberalism presents a clear solution to this problem. The government has a mandate to balance tolerance and restraint against the obligations that ensure fairness and social coherence; these equities are weighed within democratic institutions that aim for consensus through voting and other forms of civic participation. America’s constitutional order has sustained itself by becoming more liberal and more democratic over time. This model is popular if it’s anything at all.

Deneen is uninterested in the mechanisms of consensus-building. It really seems as though he wants to arrive at his preferred social and political “constitution” by fiat—the emulsion of its parts ensured by the deep wisdom of people like him.

Mr. Quackenbush, in the Study, With a Computer

The book’s obvious sin is its obtuse lack of specificity. It tells us about the “common good” and its relation to the “wisdom of the people,” but is vague about what the “good” consists in. It advocates for a “mixed constitution,” but gives no substantive examples of legal or institutional reforms that rise to the level of a “constitution,” neither in the American nor the British idiom. He champions the rise of a social class who will usher in a new regime, but proposes little in the way of practical schemes by which this might occur among actual institutions and social interest groups. Maybe Deneen wants us to guess about how all of this is supposed work, by induction, as if politics were a game of Clue. Maybe he has other material in mind, but chooses, for whatever reason, not to reference it. More likely, if he were to commit to positions that have to be defended intellectually, this would require actual ideas and some evidence, and he has none of the imagination or the expertise to make good on the book’s assertions.

He has interesting things to say about how certain class dynamics give rise to political and economic ideologies that have downstream effects. And he articulates them well. We should be mindful of his critiques, as these dynamics seems to be an engine for the Culture War that has recently consumed political life and public sense-making. But his points are hardly original, nor are they particularly deep; such analysis does not support Deneen’s Big Conclusions—that the world is disintegrating and worse than ever before, that liberalism has failed, that the “ruling class” is one of the worst in history.

He appears to have started with these opinions, and then worked backward with convenient arguments, cleverly focusing on the hypocrisies and contradictions of certain prominent social sets. In doing so, he studiously avoids contrary arguments and evidence. For example, there have been enormous strides in alleviating the worst echelons of poverty worldwide. Industrialization has consistently and dramatically improved life expectancy and dismantled child mortality from historical norms. Vaccines and antibiotics have eradicated numerous terrifying diseases from daily life, including the worst effects of the COVID pandemic from which we are lately emerging. Historically, the rise of liberalism exactly correlates with slavery and serfdom being criminalized and deemed unconditionally immoral, and consistent with this development are both the liberal ethos and the transformative demands of an industrial economy. Some Americans feel our country, as a liberal democracy, is the best place they could ever want to be.

Worse than this, he ignores the brutality of anti-liberal regimes, such as they have taken shape. Is the managerial class of the United States one of the worst ever seen in the world? What might the Uighurs in Xinxiang say about the political leadership of China? The Ukrainians who have been murdered, tortured and abducted—how do they feel about Putin’s stand against “liberalism”? Does he believe that “pre-liberal” regimes were free from systemic exploitation, cruelty and bloodletting? The Antebellum South? The British in India? The Spanish in the Americas? The Aztecs? The Mongols? Caesar in Gaul? The Siege of Melos? The Assyrians?

The implication is obscene. This is the book’s less obvious sin: that reading it is like watching an R-rated movie on TV where they’ve dubbed out the swear words. He condemns liberalism and its “elites” for disfiguring “normal folk,” but his pastoral fantasy bears no resemblance to real alternatives, present or past. He mostly conceals his ambitions for Christianity, lest the gospels contradict his objectives. His thesis, if actually tried in the world, is the same double-talk he attributes to the “liberal elite;” he is, in fact, advocating for an authoritarian program that delights in sadism and bitterness.

Ultimately, his concept of liberalism is wrong. Liberalism is a necessary condition of an industrialized, global society. It is a political attitude rather than a cultural one, and it fosters moral humility, minimum rather than ideal standards, and democratic engagement within institutions. It accepts the differentiation of society into cultural spheres with their own internal dynamics. Liberalism is not a particular set of policies or even a defined set of cultural values, but an interval of time in which these things can be contested by all and sundry without social breakdown and political violence. It defends the dignity of the individual against the arbitrariness of the social world. America has been a liberal nation since its inception, and the country’s economic strengths, and civil triumphs since the Revolution—the Civil War, the New Deal, World War II, the Civil Rights movement—have all been in service to the core liberal innovations inherent in the Constitution and the moral exertions of those faithful to democratic ideals, continuously, for two and a half centuries. After reading this book, I would not trust any opinions that Patrick Deneen has about what the common good is or should be.

Perhaps he laments the sundering of the agrarian world by industrialization, and its feudal ideas of human subjectivity. But that world is gone. It will not be recovered. There is no metaphysical “proof” that it comprehended the universe around us and our human condition better than what we might discover for ourselves should we look inward and outward—attentively. We are born strangers to the earth, and our attachment to one part of it or another is formed by our travels, as we develop and age, and by the people we meet along the way. These encounters in time and the various landscapes each individual traverses are more wonderful and terrible and beautiful and haphazard than any regime could ever prescribe.