Whatever Happened to Doggerland?

A long-lost casualty of climate change

The UK Meteorological Office’s annual look at the UK’s climate and weather reveals that sea levels are rising much faster than a century ago. Since 1900, sea levels have risen by around six-and-a-half inches—but the Met Office says the rate’s increasing. Today, sea levels are rising by 3-5.2 millimeters per year, more than double the rate from early last century.

Though these figures are concerning, surprisingly they do not represent the fastest rise these shores have experienced.

Our sceptered isle has not always been an island. Looking northeast across the oily grey gelatinous mass of the North Sea from East Anglia, it’s hard to believe that beneath the watery landscape is a lost land. But underwater is a relatively newly discovered old world destroyed by climate change. Its submersion created refugees who were among the first to arrive and settle in Great Britain.

In the early 20th century, a new design of deep-sea trawling nets started to catch the bones of mammoths from the sea floor. Remains of horses, reindeer, wolves, and bears—animals from the Holocene, our current geological epoch which started 11,500 years ago—followed. The bones were not worn or damaged in any way, as they would have been if buffeted by the tides and moved from elsewhere. They could only have been there, at the bottom of the cold, grey sea—where the animals had lived.

By the late 19th century, there was an awareness of this lost land’s existence. H. G. Wells referred to it in his “A Story of the Stone Age” which is set in

a time when one might have walked dryshod from France (as we call it now) to England, and when a broad and sluggish Thames flowed through its marshes to meet its father Rhine, flowing through a wide and level country that is underwater in these latter days.

But it had been conceived of as a land bridge, an ice age superhighway used to cross from one area of habitation to another.

Then, in 1931, the trawler Colinda hauled up a lump of peat while fishing 25 miles east of Norfolk and found the first evidence of the presence of our ancestors. The peat contained an eight-and-a-half-inches-long barbed antler point, carved by hand for hunting, which dated from between 4,000 and 10,000 BC. It, like the animal bones, was neither worn nor damaged. It was found off Dogger Bank, a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea about 62 miles off the east coast of England, named after medieval Dutch fishing boats, called doggers.

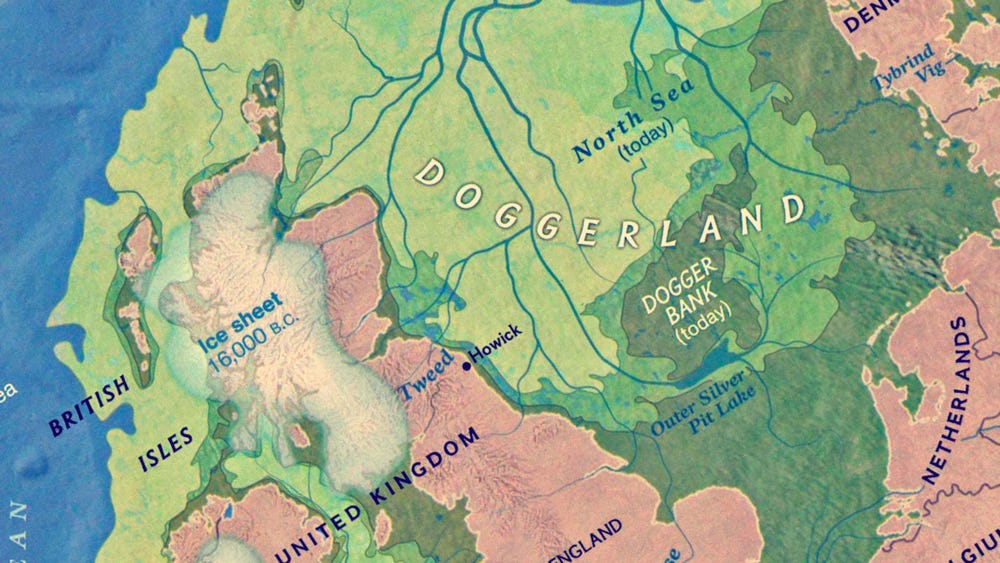

The work of Bryony Coles in the 1990s, who named the area Doggerland after “the great banks in the southern North Sea,” led to renewed interest in this lost land, and even managed to change our understanding of it. Coles liked the etymology of “dogger,” which seems to derive from the Danish word “dag,” meaning dagger. Dogwood—the pliable stems of that wood were used by Mesolithic peoples for making fish traps, while the hard heart wood was used for spears and daggers—used to grow on Dogger Bank, too. Coles produced speculative maps of the area, recognizing that due to millennia of settled sediment, the seafloor of the North Sea does not give a true representation of the topography of Doggerland. Coles described a land full of life, like the hunting and fishing communities today in British Columbia, Canada.

Between 2003 and 2007, a team at the University of Birmingham led by Vince Gaffney and Ken Thomson started to produce a much more accurate representation of this land, mapping around 8,900 square miles, using seismic data provided for oil exploration research by Petroleum Geo-Services. These geological surveys have suggested that Doggerland stretched from what is now the east coast of Britain to the Netherlands, the western coast of Germany and the Danish peninsula of Jutland, its total size like that of England today.

We have come to know the big picture story of the planet’s changing climate over the last few million years from ice cores drawn from Greenland, Antarctica, and tropical mountain glaciers that show how the climate has responded to changes in greenhouse gas levels. This is supported by evidence from tree rings, ocean sediments, coral reefs, and layers of sedimentary rocks. During the last Ice Age, which began about 2,580,000 years ago, Britain was a highland peninsula of Europe, the far corner of the continent, covered in ice, but nonetheless a part of the continent, joined by land to the rest of northern Europe. At the southern edge of the ice sheet a large lake was fed by some of northern Europe’s major rivers including the Thames and Rhine. South of this, the channel river flowed into the Atlantic. As much of the world’s water was bound up in ice, the sea level was about 390 feet lower. But as the climate warmed from 18,000 BC on, the ice began to melt.

By around 12,000, Britain, as well as much of the North Sea and the English Channel, was low-lying tundra. Herds of mammoths would have roamed the tundra, and woolly rhinoceros, saber-toothed cats, and cave lions would have shared this lost land with them. It was around this time that the eighth attempt to colonize Britain occurred and for the first time was successful. Our ancestors crossed Doggerland and migrated west to settle, as later would the Beaker people, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, Normans, Fleming, French Huguenots, Romani, Indians, Irish, Africans, Germans, Russian Jews, and then, since 1945, many more from Ireland, the former colonies including the Windrush generation, from all over Europe, and countless other groups and individuals. On a long enough timeline, we all come from somewhere else.

By about 10,000 BC, the north-facing coastal area of Doggerland had a coastline of lagoons, estuaries, tidal creeks, salt marshes, mudflats, and beaches, as well as inland streams, rivers, freshwater marshes, and lakes. It may have been the richest hunting and fishing ground in Europe, with red and roe deer, elk, and pig replacing the animals better suited to the cold tundra.

By around 9000, parts of the area would have consisted of woodland. But as the climate kept warming, the glaciers kept melting, and this caused sea levels to rise.

By 6500, Doggerland was reduced to low-lying islands before its final submergence, possibly following a tsunami caused by the Storegga Slide, a great submarine landslide in which some one thousand miles of an underwater cliff collapsed close to the Norwegian coast. Another view speculates that the Storegga tsunami washed over what was left of Doggerland, but then ebbed back into the sea, and that later North America’s Lake Agassiz burst, releasing massive amounts of fresh water that caused sea levels to rise and the final flooding of Doggerland.

Whatever the cause, Doggerland eventually became submerged, cutting off the British peninsula from the European mainland, leaving the upland Dogger Bank as an island until at least 5000 BC.

The rising sea levels, along with the warming of the seas themselves, would have caused profound changes to the nature and distribution of birds, animals, and vegetation. Woodland birds would have deserted areas where there were no longer berries or small prey to feast on. The land would have smelled and sounded different; the light would have changed as water seeped in and reflected the sun in ways land cannot. As salt water encroached it would have killed the woodland in its path; semi-submerged dead forests would have stood as harbingers of what was to come for the people of Doggerland.

The figures describing the process of the submerging of Doggerland suggest it was a slow process, a couple inches a year, occurring over generations, maybe even imperceptible within a single lifespan. However, sea-level rise is dynamic and non-linear; rapid changes can happen abruptly as thresholds are breached and tipping points reached. These radical changes happened at the local level during people’s lifetimes. The people of Doggerland would have been denied access to land they previously used to live on and would hunt in, a land that held a variety of social purposes. But none of this tells us about the experience of the people of Doggerland. How did they cope with the loss of their land? For how long did they hope the tide would turn and return what they had lost?

The archaeological evidence from the period can give us some clues. Writer Julia Blackburn, in her wonderful Time Song: Searching for Doggerland, tells us that

Everything speaks of what it has been: the leg bone of a wading bird holds the image of that bird standing on the mud of a shoreline, poised on its own mirror reflection.

Hominoid bones speak of hunger and starvation, accidents, and the efforts of carrying heavy loads that most of our ancestors experienced. You can work out that half of the children did not make it to become teenagers and few adults were older than 60. You can see that many adults, both men and women, died from violent interactions with other humans.

We can speculate that the loss of land resulted in increased tensions between groups, possibly even warfare, and we can look worryingly to areas that are today losing resources to climate change, such as desertification in the Sahel that has made key resources like water scarce and has the potential to pit group against group and country against country.

The land on which Doggerland’s residents lived, however, would have provided them with far more than the natural resources needed to survive. It would have provided these people, and these communities, with an identity. Human lives are enmeshed with place; people are embodied and located. Externalist philosophers argue that the conscious mind is not only the result of what is going on inside the brain, but also what occurs or exists outside the subject. People are embodied and located; we are in our environment and of it. When places are removed so is a person’s own place in the world. Speaking to people in war zones as conflicts escalated and communities became torn apart, I often heard a reticence to accept that the place they once knew had gone. There was often hope that the fighting was a brief anomaly and things would return to normal that persisted past the point when it should have been clear that the conflict was now embedded and there was no going back to how things once were. Sites of concentrated deposits of Mesolithic weapons and tools in liminal areas in Denmark and the Netherlands suggest ritual offerings were made by those in coastal communities with similar hopes, to placate the rising tides.

Doggerland was more the natural resources it offered its people; it housed the memories of generations, the binding narratives, the community myths that were also written into its land and wildlife. When we look at migrants today crossing the now-flooded Doggerland, the focus is on what they are coming to take from the UK rather than on what they have lost. The people of Doggerland lost the land that was the resting place of their gods, the birthplace of their kin, the place of burial for their ancestors, and filled with community landmarks rooted in the earth. It’s not possible to supplant these onto a new land as if we’re dealing with interchangeable parts, but it is natural to try when you reach your new home. Those fleeing war and persecution today and climate change in our near future will suffer similarly precious and intangible losses. How were those now-placeless people who left Doggerland seen by those living in the lands they migrated to?

Whether you believe climate change is just a natural part of wider climatic cycles or the scientific consensus that it is being impacted by man-made activities, our climate is changing and at an accelerated rate. Doggerland shows how profound the impacts of climate change can be and how long those impacts can last. Sea-level rises are already threatening the homes of millions of people in the tropics. Current global predictions suggest a further sea-level rise of one meter in the next century. Currently 267 million people worldwide live on land less than two meters above sea level. By 2100, with a one meter sea-level rise and zero population growth, that number could increase to 410 million people. A 2020 survey published by Climate and Atmospheric Science, which aggregated the views of 106 specialists, suggested coastal cities should prepare for rising sea levels that could reach as high as five meters by 2300. The impact of increasing temperature rises will make water one of the most valuable and fought-over resources on the planet and put great pressure on arable land.

In some of the areas today most at risk from climate change there are also nefarious actors deliberately fostering conflict. Last year, Russian President Vladimir Putin used the flow of migrants from Belarus into Europe as a weapon to sow disunity. The president of Belarus, a Russian client, threatened to flood the EU with armed migrants. Belarusian authorities started promoting tours to Belarus and giving those who bought them Belarusian visas, and then advice and bolt cutters to make their onward journey. The Wagner Group, the private military organization seen by many analysts as an unofficial foreign policy tool of the Russian government, are now influencing conflicts across the Sahel, including in Libya, Mali, Central African Republic, Sudan, and Burkina Faso—all countries that are losing thousands of acres of farming land a year to the expanding Sahara Desert. By gaining influence in these countries, Russia is now able to manipulate conflicts and refugee flows into Europe for decades to come.

Today we may be an island, but that will not stop people from coming across the sea that now covers the ancient pathways of Doggerland to seek sanctuary from changes outside their control. Climate change is often spoken of in terms of the scientific measurements, maximum temperatures, and levels of sea-level rise. But this is not how people experience it. People crossing the channel today will drop possessions to the bottom of the sea. Tragically, some of those will end up settling on a seabed that was once land. Some of these will resurface over time. But if we don’t take the effects of climate change seriously, there will be no archaeologists of the future to find them. If people in the future do find a way to counteract some of the worst climate prognostications and extend the viability of the human race, hopefully they will not have to speculate what our hopes and fears were, as we unfortunately must when thinking of the hopes and fears of the people of Doggerland, whose experiences are lost to history.

Looking across the North Sea, gently undulating under a summer breeze, the sun’s liquid rays dancing like infinite pods of dolphins porpoising through the swell, it is hard to believe that 300 feet below, people used to live, love, and die. Before a profound change it is often hard to conceive of its possibility. Maybe that’s what Doggerland can do for us. Maybe it can help us see the shape of the world ahead, and what we must do if we are to keep it.